This section has selected published work by or about Primalise.

The First 3,000 Days of Life – Integrating Living, Learning, and Livelihood into an Elegant Nested System

What if living, learning, and livelihood weren’t separate but part of one elegant, nested system? Reva Jhingan Malik invites us to rethink childhood as a seamless, instinctive journey—one where play, curiosity, and connection naturally shape a child’s foundation for life.

(This article builds on the learnings from EkStep Foundation’s Early Childhood Project that Primalise has been part of; and is also a consolidation of the key insights into living, learning and livelihood that Primalise has gained over the years.)

“Can you see a cloud floating in this sheet of paper?” Thich Nhat Hanh, a Vietnamese philosopher, posed this question to illustrate the interconnectedness of everything around us.

Considering this, can we view living, learning, and livelihood as a single, integrated life system? We invite you to explore the interconnections and synergies within this nested life system. This system encompasses all our experiences and provides a rich foundation for learning across all age groups, particularly in early childhood, when children are beginning to make sense of their world.

The Fragmented Reality

Currently, the three subsystems – Living, Learning, and Livelihood – each with their own structures, orders, and values, operate separately in silos, missing out on potential synergies.

Living environments, especially modern households, are often insular and disconnected from the wider community. Within these homes, spaces are compartmentalized, leading to disconnection among family members.

Learning predominantly occurs in schools and educational institutions, which not only keep young children away from their families for most of the day but also often turn them into passive recipients of knowledge rather than active participants. This dependency on receiving information persists for far too long.

As for the livelihood subsystem, it is frequently removed from both living and learning spaces. The skills and expertise acquired for earning a livelihood often remain inaccessible to these environments since work typically occurs in separate settings.

This fragmentation insidiously disrupts our interconnectedness, which is essential for a cohesive society. When interconnectedness is lacking, individuals may feel fragmented internally. A cohesive society with strong family units provides a secure environment for children to grow up in. Conversely, an insecure atmosphere can foster a toxic culture characterized by a scarcity mindset, mistrust, unnatural competition, and narrow benchmarks of success.

Reconnecting with Our Core Essentials

What is Our Normal?

When the super-normal becomes normalised, what we once considered normal appears sub-normal. Our fast-paced and highly efficient world increasingly marginalises normalcy, overshadowing average intelligence. In a context of systemic compartmentalisation that alienates individuals and societies, it is crucial to reconnect with ourselves and our authentic human nature – our normal. This reconnection encourages us to value what we have and who we are while fostering respect and inclusivity.

Returning to normal demands a fundamental shift in our mental models around learning—a shift from a mindset of:

• Scarcity to Abundance – of time, space, resources

• Inadequacy to Adequacy – of abilities of children, parents, caregivers, teachers

• Denial to Acceptance – of the child’s uniqueness and our own

• Exclusion to Inclusion – of differences and diversity

Isn’t it time we recalibrate our understanding of normal?

Normal human nature, normal human pace, normal human scale.

This recalibration is what our children will absorb as they grow up in this environment.

Inducing Learning?

Are we rushing to transform children into students? Forcing structure too early interrupts natural processes designed to provide children with a solid foundation. Learning occurs when children interact directly with nature and culture; their first-hand experiences resonate more deeply than second-hand or processed encounters. An excessive focus on ‘education’ at an early age deprives children of rich multisensory engagement with the world around them.

In an ideal setting, learning is a natural consequence of living; sadly, we have turned it into an intervention. Humans are the only species that confine their young ones into rigid time and space boxes for indoctrination. In our pursuit of recognition and validation, we inadvertently push our children onto the same treadmill we ourselves run on.

Isn’t it time we reconsider learning as a life process?

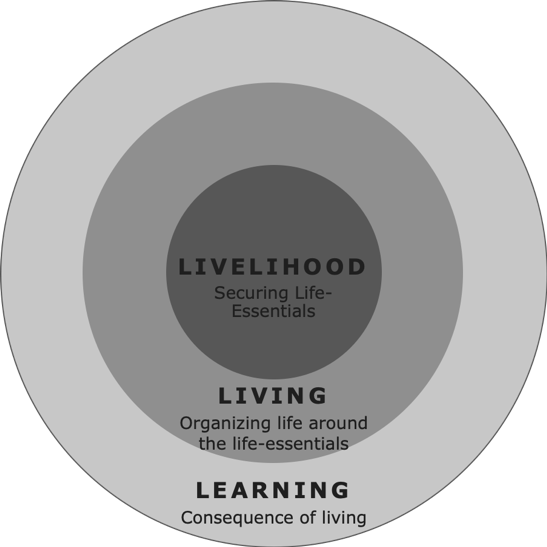

If learning is part of the nested life system where livelihood, living, and learning overlap, then early childhood learning need not be artificially induced; rather, it should occur naturally. In this elegantly congruent system, livelihood focuses on securing life essentials, living is organized around these essentials, and learning emerges as a natural consequence of both. Here are some principles this system will follow:

- Children are not merely adults-in-progress; they are childhood-ready – prepared to be, do, relate and grow.

- Active feedback loops are nature’s way of fostering self-reliance in children. During early years, children engage in fascinating processes that build complex feedback loops that stitch the essential interconnections within and between living, learning, and livelihood sub-systems.

- We live life; we don’t ‘do’ life. Similarly, learning is not something you ‘do’; it happens organically. Modern living often feels overly deliberate and designed; however, the best learning arises as a natural outcome of living.

Loss of Instinct?

The early childhood years – the first 3,000 days from birth to age eight – form the foundation upon which one’s life journey is built. This foundation allows individuals to reach their full potential. The pace of growth during these years is unparalleled throughout life; it provides children with the foundation for age-appropriate self-reliance. During this critical phase, foundational instincts develop – instincts that empower children with the agency needed for self-reliance.

Are these instincts inborn, imbibed or induced?

The foundational instincts that develop in the first 3,000 days are in various degrees inborn, imbibed, and induced.

- Natural instincts are inborn.

- Cultural and occupational instincts are imbibed and induced.

In most living beings, development during the initial stage of early childhood is essentially led by and rooted in natural instincts; the development of cultural and occupational instincts follows.

These instincts should take root at appropriate times; well-rooted instincts lay the groundwork for future success. It is suboptimal to induce skills that should ideally be imbibed through experience. Activities of daily living (ADLs) are best learned through natural engagement rather than forced intervention. Unfortunately, many children today experience suppression or weakening of innate behaviors due to inhibitive conditions such as insecure upbringing or performance-related stress stemming from societal challenges like discrimination or competition.

A healthy childhood requires the richness and abundance of a holistic ambience where instincts can unfold naturally. Instincts flourish through unstructured play—play that children lead themselves without adult intervention or expectations. Such play engages all senses and fosters curiosity and autonomy while allowing confidence to grow.

Play is Primal. Play is instinctive. Children don’t play to learn; learning happens while they’re playing. This is not structured play; this is the ‘attitude’ of play, the idiom of play. Learning happens first-hand, the child gets experience of everything, and everything is in the child’s grip. It’s self-initiated, the child enjoys the whole learning process, and instincts are at play. There’s an age appropriateness for these instincts to unfold. Play allows this essential opportunity, space, and time.

The optimal ambiance for childhood is simply childhood itself – Bachpan. Nature ensures that both child and family are instinctively prepared for this stage. Childhood must be recognized as a complete phase worthy of respect and celebration – a celebration long overdue: 3,000 days dedicated to honouring childhood – Bachpan Manao.

Our Commitment to Our Children

Vibrant first-3000-days should be every child’s birth right and the society’s responsibility. This could be our manifesto for change:

Nature ensures that the child and family are instinctively ready for childhood. The first 3000 days of life help the child build foundational agency to become self-reliant. Fair access to an enabling and responsive 3000-day support system is every child’s birthright and the society’s responsibility.

This support system must include all carers – natural (family), social (community), health (medical) and learning (pre-school/school). Lack of access to it could lead to a child going through cycles of underachievement, which widen achievement gaps and further restrict opportunities through life—a precarious agency-robbing downward spiral.

Seamless access to it will put every child on an agency-enhancing upward spiral.

And this is the minimum we owe to our children.

This article was first published in the Bachpan Manao website of the EkStep Foundation

Forget Work-Life Balance

Find Living-Learning-Livelihood Congruence

Reva Jhingan Malik

Mental models are algorithms of the mind. They are deep-rooted thinking constructs that govern the way we make meaning, and make choices. How did separating work from life ever become a mental model? It goes back to early 18th century. The Industrial revolution introduced the concept of ‘factory system’, which required large number of workers to travel from their homes to a central work location every day. For the many generations that have followed, it has been the normal they were born into; one they have taken so for granted that the contrary feels abnormal. So much so that the stress that the frustrating pursuit of finding balance – work-life balance, feels normal too. It is a given that perhaps never got challenged.

Time to challenge the ‘work-life balance’ mental model?

Let’s try and make sense of this work-life phenomenon.

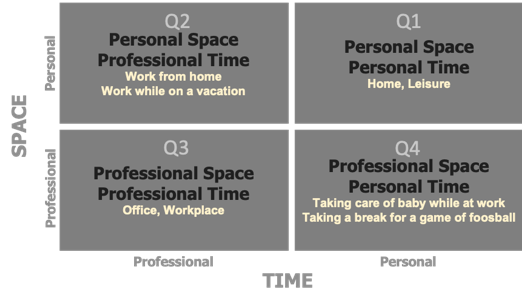

When it was introduced, the factory system sure must have taken folks then some getting used to, but the issue of balance was much simpler back then. Q1 was exclusively about home and around – family, leisure and chores, and Q3, for nothing but work. Q2 and Q4 were virtually nonexistent. Balance was embedded in the system by design – you clocked in and clocked out of the factory at fixed timings. People typically put in 10 hours of work daily. The balance 14 hours were for Q1, undisturbed.

Stress arrived when the productivity metric – the input-output ratio, became the primary focus. The factory system, as is its nature, began extracting increasingly more out of each factor of production. Labour as the softest of them all, yielded to the pressure. Q1 became the obvious victim of this squeeze – workers prioritized work over life. The perks of the work-space ensured that we greedily kept drawing time from Q1 beyond healthy levels.

While all this was happening, new kind of organizations that were a bit more worker friendly, were being born. Unlike the legacy organisations, the new ones were pretty fine with Q2 and Q4; some even offered these as employee privileges. Covid normalized Q2. And how! With it, the angst-ridden workers saw something they just couldn’t unsee – that they have been blinkered all these years; and that trying to balance work and life is a futile pursuit. These realisations led to workers asking a question that was long overdue – ‘What would be a healthy way to organize life?’

This is where we are today.

The answer might lie in understanding how human beings organized life when we lived more in sync with nature. We could try looking for key patterns in the way we have historically dealt with it.

If we look at three very distinct phases of human evolution – the forest dweller – hunter-gatherer phase, the rural dweller – agricultural phase, and the urban dweller – industrial phase, we’ll see a pattern. Humans organise life around life-essentials – water, food, energy, habitation. Once these are secured, other aspects of living are organised around them. As the system matures, it learns. And as the feedback loops begin delivering, efficiency and efficacy of its processes improve; new synergies emerge, and the system acquires a wondrous complexity.

This is what the core human life-system looks like; it’s a nested system, and not sharply partitioned:

Livelihood (securing life-essentials) is followed by Living (organizing life around the essentials); Learning (through active feedback loops) is a consequence of Living

How did we end up with a broken-down system, with three subpar fragments?

Livelihood, living and learning are three interrelated subsystems of the life-system. As we navigate our way through life, we naively begin looking at these as three separate silos; three partitioned worlds within our world. We find our own ways to be appropriately present in each; often feeling torn between them. We even feel compelled to cultivate three very different personas of ourselves to fit into the three worlds.

By its definition, a system is a whole; as Aristotle put it, “a whole that is something besides, or other than, the sum of its parts”. In elegantly designed systems, it is greater than the sum of its parts. Cleave an elegant system and you don’t get multiple equally elegant systems. “Dividing an elephant in half does not produce two elephants”, says Peter Senge. If you try artificially separating livelihood, living and learning, you will have a broken-down system, with three subpar fragments.

The standard template that modern lifestyles follow, makes fragmented life-system the default. Living is mostly insular, in houses socially cut off from the larger community, with family members in their own separate spaces within. Learning happens somewhere else, in educational institutions. And livelihood, at yet other spaces that are removed from both living and learning spaces. Each of these spaces follow their own structure, order and values, which are often not congruent with each other.

The unintended consequence of this artificial partitioning has been that we don’t see the synergistic interrelatedness of the three subsystems. We are neither in touch with the whole nor the cyclicity of the processes that run across them. The resultant incongruence causes stress.

Forget balance, find congruence

Human body is a complex adaptive system with its subsystems in perfect congruence with each other, and with the whole. The culture that envelops us, is a manmade system that is made up of manmade subsystems. When it comes to congruence, manmade systems aren’t able to do as well as nature-made systems; at least not yet. Incongruence between who we are inside, and how we are in the constructed world we live in, is the root of a lot of stress we go through. This might also be the cause of the inexplicable sense of alienation that many of us often experience.

The solution might be surprisingly simple – just mimic nature-made systems when building the life-system. We don’t have to redesign our life from scratch, we just need to tweak our current life-system, and reorganize its building-blocks.

If livelihood, living and learning are in-tune with each other, and with nature, life must just flow. The way it does for our fellow beings in the web-of-life.

If everyday living can nourish us enough physically, mentally and socially, we wouldn’t need artificial supplementary processes like, say a gym routine to keep us fit; our life processes will.

Modern lifestyles tempt people to outsource natural life-processes – daily chores like home-care, self-care, family-care and securing essentials. These processes keep us meaningfully engaged physically, mentally and socially. Absence of such activities leads to a fulfilment void that gets filled up by supplementary processes and surrogate activities that keep us busy the whole day. The resultant busyness only saves us from the fear of emptiness but is hardly satisfying at a deep level.

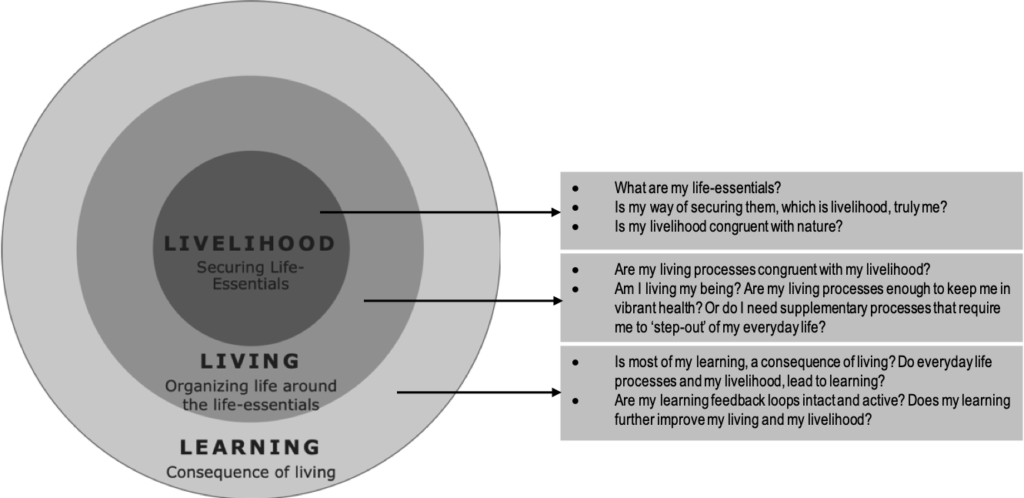

Here are some questions that might help us re-tune our life-system to congruence:

A truly congruent life-system doesn’t need to be driven, it is self-driven, self-directing and constantly evolving. If we find ourselves doing living, doing learning and doing livelihood, we might not be living a congruent life. After all, we don’t do life, we live life.

A version of this article by Reva Malik was first published in Mint on 16th January 2024

Time to Normalise Normal Again

We need to begin designing systems that elegantly integrate the needs of the society with the integrity of nature. Systems where each entity has the ability to survive on its own and keenness to come together to thrive. Both independence and dependence are enemies of interdependence.

For a world that has normalised the supernormal, normal is subnormal.

When we celebrate supernormal pace, abilities and scale, we make the normal feel inadequate and undesirable.

It’s been fashionable for those who consider themselves ahead of the curve to jump on to the next oddity, and in a superior-than-thou manner welcome others to the ‘new normal’. Thanks to the enforced stay-at-home slowdown, the world is realising how far we have strayed from the normal that truly matters.

We have been stockpiling stuff that now seems more desirable than essential, and have an acute dearth of the real essentials.

Modern urban homes are no less equipped than intensive care units. We live in sanitised cocoons with piped ‘essentials’ and become dysfunctional the moment the supplies are disrupted (exaggerating slightly to highlight).

These homes house people with amazing supernormal abilities in narrow, often abstract fields and are amazingly subnormal when it comes to surviving in nature as normal human beings.

How did we get here? The current unexpected pause in our usually planned frenetic lives is helping us take a systemic view of things.

Division of labour worked well, but have we allowed it to go too deep?

Adam Smith described division of labour as a dynamic engine of economic progress that leads to substantial enhancement in the productivity of the individual and the collective. Émile Durkheim insisted that this is how the nature functions anyway – interdependent living beings that are part of the web of life.

No doubt, division of labour led to a step-change in general affluence and access to conveniences, there have also been voices that have pointed to the negative impact of this key governing principle of capitalism if it gets too deep.

Karl Marx highlighted social and economic alienation of people who feel estranged from their own Gattungswesen – ‘species-being’. Henry David Thoreau felt it ‘removes people from a sense of connectedness with society and with the world at large, including nature. He claimed that the average man in a civilized society is less wealthy, in practice than one in “savage” society. According to him self-sufficiency was enough to cover one’s basic needs.

The essence of division of labour is interdependence, which definitely is better than isolated independence. The whole as they say, is other (greater, in healthy systems) than the sum of the parts. But what happens when unbeknownst to us, healthy interdependence gets insidiously replaced by debilitating dependence?

The Covid 19 episode might be transient, but it is starkly showing us how miserably dependent we have become on our socioeconomic systems. Very few urban people in the world today have the natural human ability to engage with nature directly in order to access essentials required to survive, the way it was supposed to be.

We built these systems to enhance access to natural and manmade resources. Over time the system became a world in itself. Supposedly ‘superior’ and more ‘evolved’ compared to the ‘raw’ nature outside of it. Sophisticates that the system produced became a new cultural class, and sophistry, their newfangled worldly talent.

In comparison just look at the primitive tribes around the world. In spite of evolving far apart from each other, their behaviour and lives aren’t very different. This is because their ‘operating system’ is the same – the Earth’s biosystem. This stood out glaringly during the earthquakes and the tsunami that followed, in 2005. Ancient indigenous tribes of Andaman and Nicobar Islands were the only communities in their region that could save themselves, using their native knowledge of wind, sea and birds. They were more surefooted as compared to the arrogant developed world around them which was clueless during the tsunami, and deservedly chastened post the act-of-God.

“They can smell the wind. They can gauge the depth of the sea with the sound of their oars. They have a sixth sense which we don’t possess,” says Ashish Roy, an environmentalist and lawyer working to protect the rights of the tribes from the world outside.

An operating system fuelled by insecurity

The developed world is the way it is thanks to the operating system it has built for itself. Economy, not ecology runs us. Consumers and producers live here, not citizens.

Each one of us plays two roles – factor-of-production and unit-of-consumption. The system rewards us when we follow good behaviour and penalises us when we don’t. An ideal factor-of-production is a person who offers maximum labour and demands minimum price for it. And an ideal unit-of-consumption, the one who consumes more than the rest and also pays generously for the goods and services that the system produces. Materialism is the guiding philosophy here and productivity the currency which dictates all choice making at macro and micro levels.

Now let’s zoom in on this ideal being and you will notice something surprising, but not so much in hindsight, insecurity.

Professor Laura Empson, of London’s Cass Business School, who has been researching leaders in elite professional firms and financial institutions, says this about successful, driven professionals:

“Many of the professionals in this world are ‘insecure overachievers’: exceptionally capable and fiercely ambitious, but driven by a profound belief in their own inadequacy. Their ability and relentless drive to excel make them likely to succeed in the competitive environment of elite professional and financial firms, but the work culture is also taking advantage of their vulnerabilities.”

As consumers, the system loves the selfworth deficient. After all, isn’t all that you have on you a reflection of all that you don’t have in you? The system constantly works at finding ingenious ways to keep the consumer that way and monetize the deficiency.

The production-consumption system must grow for its survival. And in order to continuously grow, which is unnatural, it pushes the factors-of-production to up their productivity, often at the cost of their own wellbeing. It introduces competition among them to make them push their limits.

It’s an autopoietic system, it rewards its insecure factors-of-production with its own produce; and helps itself further by making the factors-of-production spend their earnings to feed their insecurity by becoming its consumers. This insatiable insecurity is the bottomless well that fuels the system.

It would be catastrophic for the production-consumption system if people were to become secure in their minds and begin consuming only as much as is essential.

The sense of insecurity flows through generations. Anxious parents curate customised lives for their children. The factory model education system produces just the kind of compliant, insecure humans that the production-consumption system needs. It becomes a training centre for the producers-consumers of tomorrow, and the curriculum, nothing more than an operations manual of the tiny part of the giant system we ‘choose’ to super specialise in.

As a super specialist, we are not expected to understand the workings of the larger system. In fact as per the grand design, we aren’t supposed to have the time, ability or motivation to do so. We are kept occupied on the constantly running treadmill and lulled into a comforting trance. It’s our couch, difficult to move off from.

“It is no measure of health to be well adjusted to a profoundly sick society.”

J Krishnamurti

Have we normalised the abnormal?

Eckhart Tolle says, “stress is being here when you want to be there.”

No wonder most of the world hates Mondays. After all we are where we don’t want to be. We wish to be somewhere else, or even, often, someone else in life.

Instead of living with the stress of perpetually striving to catch up with the grotesque ‘desirable normal’ that the world has defined for us, wouldn’t it be saner for each one of us to find our own normal, and just be? Not the felt normal or the wished normal, but our true normal

Let’s primalise to find our own normal

Primalising is not about going back, but about going deep. It is about reconnecting with, to use Marx’s term, our Gattungswesen – ‘species-being’ or ‘species-essence’. It is about living a congruent life. About living our being.

The human race has come a long way. Our ingenuity has produced some truly meaningful innovations over centuries. We are in an interesting position to reset our world. To reimagine it by picking the most elegant combination of mental, social and physical artefacts that took ages to build.

We need to begin designing systems that elegantly integrate the needs of the society with the integrity of nature. Systems where each entity has the ability to survive on its own and keenness to come together to thrive. Both independence and dependence are enemies of interdependence.

If we don’t want to waste the good crisis we have on our hands, we need to do it now, otherwise we will find ourselves on the treadmill again.

This article was first published in Business World on 29th April, 2020.

The Lockdown Is Going Soon, But The Virus Isn’t. We May As Well Rebuild Our Meaningplex.

The new world we are headed to isn’t too different from the world we grew up in, but like it happens in the alternate universes that intriguing fantasy fiction sprouts from, one little quirk has been introduced to make things interesting – humans here are allowed to be just human, and not superbeings, as is our wont.

This has been a forced pause. Like most impositions, this one too is being resented but not being outraged against. You need someone despicable to direct your outrage at. But there is none of the kind here; just a virus, busy being a virus.

As we haven’t felt much hatred towards it, we have gotten busy getting to know this new arrival without much malice; and have also gotten down to reorganising our lives knowing that the virus isn’t going away in a hurry.

We are all in transit. Currently on a one-way bridge between two worlds. All seven and a half billion of us have been pushed on to it by an insignificant sized microorganism, and that is something we are struggling to come to terms with. We are, after all, the superbeings who run the Earth.

The new world we are headed to isn’t too different from the world we grew up in, but like it happens in the alternate universes that intriguing fantasy fiction sprouts from, one little quirk has been introduced to make things interesting – humans here are allowed to be just human, and not superbeings, as is our wont.

That shouldn’t be tough, right? We just have to be us. There is a minor issue though, we have too many modern definitions of what it means to be human going around. And to add to the challenge, our favourite definitions and nature’s definition don’t match.

Who caused the mismatch? Not nature, not our fellow earthlings, perhaps unwittingly (and in many ways deliberately) we did as we evolved and acquired sophistication. Our definitions come from our cultures. Nature is what we were born to and culture is what we crafted. Through generations of not just everyday being, doing and relating, but also living through pandemics and phases of vibrancy; through wars and revolutions.

We live in our meaningplex

Our culture is our life organising system, our meaningplex – a complex yet coherent matrix of meanings, complete with its values, norms and artefacts.

It is our interpretation of reality. Often incongruent with nature’s interpretation of it, but we haven’t let that bother us. In our usual self-entitled way, we have decided that we get to decide the kind of reality nature and all her other beings must live in.

We have taken our meaningplex too for granted for too long for us to notice its flaws that have now begun to show. Its foundations suddenly seem unsure. This is forcing us to critically examine the grand structure itself.

We’re questioning our own mental models. We’re also readily indulging in thoughts and activities that we have been dismissing as impractical all our lives. Some of us are rather chuffed with our newly discovered talents.

How about we first deconstruct our world to reconstruct it?

While we might be waiting to get back to many of our usual ways as soon as we can, this pause has led us to think broader and deeper; and could leave our lives altered in ways we have never imagined. It is a rare opportunity for us humans to reconnect with our humanness and to reconstruct our lives grounds up.

Times like this allow us the license to challenge even the unchallengeable. Some wisdom that has been handed down to us as facts and truths, we now realise, was really just opinions.

It is time for us to ask ourselves questions that will help us separate the true-essential from the felt-essential. Even mundane questions like, ‘is physically lugging our whole body to work every day, essential?’ would lead to interesting possibilities.

Organising our lives around our true essentials

We have configured our lives to a synthetic world that follows a pace, scale and character that is hardly human anymore.

If we are reconstructing our world, why not reintegrate it with nature? As nature’s beings, we are today the most precariously dependent ones. We have lost the ability to be led by our instincts. For almost everything, we need our artificial system that thrives by keeping us dependent on itself. And it is an unhealthy dependence.

A months-old baby monkey knows which fruit to eat and when, and in comparison a human baby even at 40 is lost without help from a nutritionist or an app. Very few urban people in the world today have the natural human ability to engage with nature directly for accessing essentials required to survive, the way it was supposed to be.

Let’s look at two examples of our old world’s felt-essentials – fighting BO, and schools.

Fighting BO

Being locked down at home alone, we have been using far less deodorant, and surprisingly not missing it much. How essential is it for us to mask our natural human smell all the time – waking hours and sleeping? Given that the world spends USD 80 billion on deodorants and antiperspirants every year, it must be super essential!

If we were to map this product on the human evolution timeline, it would look too trifling to be called an essential – the first deodorant was trademarked in 1888. For a long time even after this product was introduced people felt (or knew?) that it was unnecessary, unhealthy or both

Think about it, in a world where all stink, no one smells.

And this is a product that exploits our insecurity – ‘your natural human smell is offensive, it will come in the way of your success’ is what we have been made to believe. Why in the world have we been supporting an industry that thrives by keeping us self-worth deficient?

Back to school?

School is a manmade social artefact that we believe is essential to our lives. The question is, ‘is coercing and bribing children through pedantic curriculums that focus more on forced teaching than natural curiosity led learning, essential?’.

We are the only species that pushes its little ones into boxes, to artificially induce into them motivation and knowledge in order to prepare them for a certain future we have naïvely predicted for them – a world that runs not by ecology, but the economy. Where growing up to be a factor-of-production and a unit-of-consumption is essential, and being part of nature’s web of life, optional.

Disposable ‘essentials’

Here’s a broader (and deeper) question worth asking today – ‘If everyday living could nourish us enough physically, mentally and morally, would we really need artificial supplements like gyms, schools and temples?’

There is a lot of dispensable old-world stuff we needn’t carry with us into the new world.

Not just things, but also habits, attitudes and belief systems. We have been cultivating these for years because we were sure these were essential for us to succeed; aggressively competing with each other to earn trappings that feel non-essential, even vain, in hindsight. And what’s indefensible is that we have been chasing the stuff at the cost of all that is truly essential.

It won’t be easy for us to let go, we will do our best to hold on to the old-world felt-essentials. Just look at what we have begun doing with schools since the lockdown. We are clumsily mimicking the flawed factory model schooling system using our newfangled digital tools and are waiting to push our little ones back on to the assembly line.

But shed the ‘precious’ baggage we must. Perhaps we need to get old-world poor before we can get new-world rich.

This article was first published in Business World on 6th June, 2020.

Primalising is not about going back, but about going deep. It is about reconnecting with, to use Marx’s term, our Gattungswesen – our being. It is about finding congruence, as an individual, institution or business. About living our being.